Redis is forked

Hey friends. I need to do a better job keeping this newsletter up to date instead of posting random links on five million social platforms, each of which now have three users each.

Since my last email, I've written:

A short post on perception in groups of humans

Shared some of my work on LLM evals

And shared that I was keynoting at PyCon Italia

Do people prefer getting these in one-offs as separate emails? A bunch all at once? Are long technical posts as emails okay? Let me know. Still figuring out what works best in this New Media Landscape. Anyway, on to what I posted on the blog today, about Redis.

Redis is forked

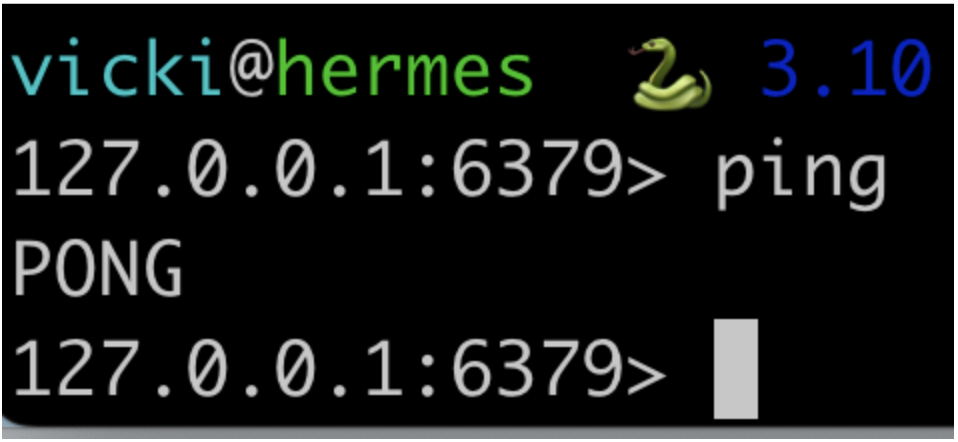

I, like many developers who have worked on high-scale, low-latency web services over the last fifteen years, have an intimate relationship with Redis. At any new job, when you ask where the data is, and someone points you to a server address with port 6379, you know you will meet an good, reliable friend there.

When you shell into the redis box or container or pod, you know what you’re going to find. When you run redis-cli, and it, immediately, presents you with the >, you know you’re ready to work. And, when it returns PONG to your ping, you are filled with a sense of ritualistic completion and assurance that it is as ready to read your code as you are to write it.

I have been running ping now across countless Redis installs, across web services written in PHP, in Go, Java, in Python, (unfortunately) Scala, across industries, across space and time, across multiple products that use and have used Redis as cache by default.

I, as a cynical Eastern European, hate almost everything in software. But I love Redis with a loyalty that I reserve for close friends and family and the first true day of spring, because Redis is software made for me, the developer.

Everything about Redis is meant to empower, to clarify, to show, where abstractions need to be shown, and neatly tuck them away where they don’t. It is made to work, to handle my throughput and stay out of the way.

Even the documentation is written for developers who want to learn more, not to obscure or to sell.

I used it at work, and I used it as my vector search engine in Viberary, where it worked brilliantly and with extremely low latency out of the box. In a world full of junk, bloated, and obfuscated software, Redis just works. Or, as the best software developers I know would say, it is elegant.

Unfortunately, my Redis doesn’t make money. While I was working on Viberary, I remarked to friends that Redis was a better vector store for probably 80% of use-cases than actual vector databases, and that it was a shame that the Redis Search module wasn’t well-known. Of course, in the heat of the generative AI landscape, the monkey’s paw curled, the over-leveraged business decided they needed to actually make money, and they changed the license, ostensibly so that AWS and other large-scale cloud vendors couldn’t sell it as a product offering.

In a pattern that has previously happened for Elasticsearch and Terraform, and one that was extremely predictable, Redis is now forked at least three different ways - the original Redis, now no longer under BSD, Valkey, under BSD and led by previous contributors to Redis from AWS and other companies, and Redict, under GPL, led by an open-source coalition. Both of these licenses allow commercial reuse.

The old Redis was for developers. The new Redis is for enterprise sales, and for generative AI. It’s true that it’s not yet entirely clear what all of this means for the future of Redis the software. Some say the licensing changes won’t impact much if you’re not a large-scale Redis reseller. Because it’s true that the license changes were all legal and all parties acted in accordance with both what’s acceptable and what the market dictates to sustain the software. And yet at the same time, projects that depend on Redis are withholding updates or migrating.

But the problem is not only that the license changed suddenly, without warning, it’s the messaging behind the change, and the message is, even though there is extremely active community development, Redis is no longer in and of the community. We are no longer being consulted.

As for the forks, there is no clear direction yet either. Valkey is on GitHub and already extremely active, yet there is already a debate about what OSS means in the context of the fork. Redict is entirely open but has opened contributions on Codeberg, where they are far from GitHub’s AI training data collection, but also miss out on the network effect for contribution in the GitHub social network, the friction of which can’t be underestimated.

All of this is very sad, because it’s not clear which path forward makes sense in this new landscape for me as a builder if I want to now use Redis in a new project, particularly since neither of the new projects support modules like Redis Search yet. (Or if they do, it’s not clear to me whether it’s directly drop-in compatible and what the licensing issues are there.) It seems like the new, corporate Redis is no longer for me or my personal projects, which is ironic given that my interests lie squarely in the vector search and generative AI spaces. It’s also not clear if I wanted to contribute, which one I should give my time and energy into. So, it seems like I’ll be staying on the Redis available before this commit for the time being, until the dust settles.

Good things don’t scale, except in the case of Redis, where all it does scale in O(1) time, but doesn’t align with the realities of markets in software.

Fortunately, in redis/valkey/redict codebases, one thing that is still a constant is that whenever there is a ping, you can always expect a quiet, resounding pong, and in that regard, with the current energy around open-source, particularly in the ML space, I’m optimistic.